Fellow Actors, nobody wants to sit through a stilted performance of a lifeless monologue. There is something wrong when the actor is the only person who really knows and enjoys what’s going on.

On the other hand, there is nothing more fascinating than watching an actor embody a character through monologue successfully. It’s incredible when he/she presents the character’s thoughts through his/her physical presence, imagination and inner activity – not just the words of the monologue.

This being said, here are helpful guidelines I summed up from legendary Uta Hagen’s take on performing monologues. By monologues, I mean any scene in which your character is alone in a given time and place and finds him/herself talking out loud for a specific reason at a moment of crisis.

First and foremost, it’s important we know:

WHY WE TALK TO OURSELVES

Talking to ourselves is always an attempt on our part to gain control over our circumstances.

These circumstances can look very different. They can be boredom or a tragic situation.

For example, when I’m in a hurry, my verbalisation of, “Ok, I’ve got my keys, my wallet… where’s my phone?” is merely my attempt at organisation. In the case of a dramatic monologue, Uta Hagen explains “it’s that you are in crisis and need the words to help you find answers.”

So, when you tackle your next monologue, make sure you determine and are aware of your circumstances – or your ‘crisis’.

The next important aspect is observing yourself and others and knowing:

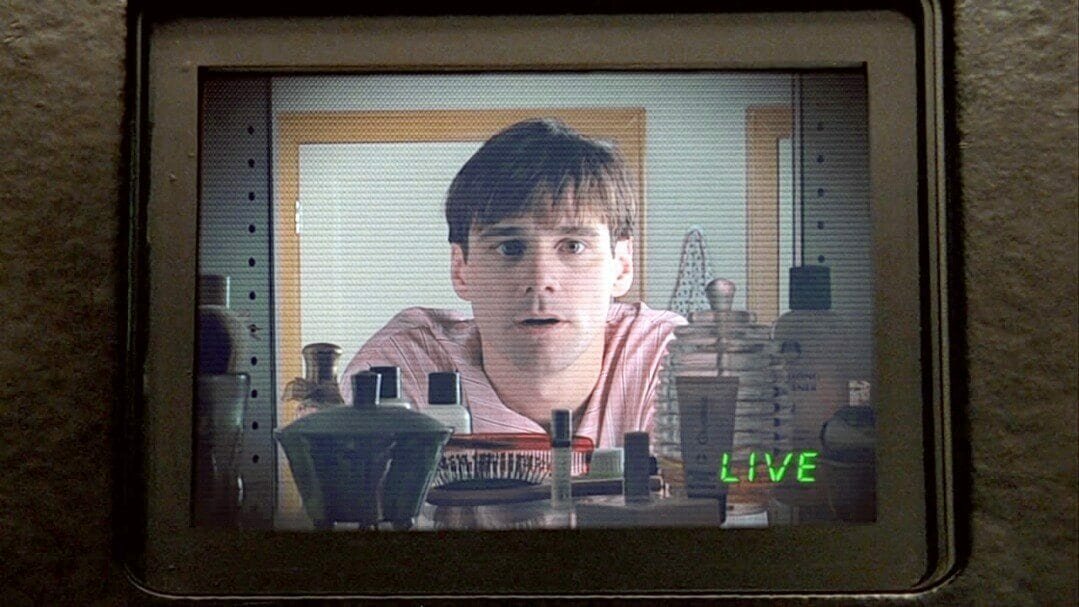

WHAT TALKING TO OURSELVES LOOKS LIKE

A big temptation for actors is putting too much emphasis on the actual words. Uta Hagen describes it as “mostly a subconscious procedure that makes you verbalize” because it is an involuntary process, most of the time we’re not even aware of it.

Because we are often so caught up in our thoughts, words are merely the byproduct of trying to figure out a situation, or an emotion we are submerged in. It is, in other words, an overflow of our thought process about the circumstances we’re currently in or an experience we’ve just had.

This is why it always important to take into consideration that:

OUR WORDS NEED PHYSICAL PRESENCE

In her book Respect for Acting, Hagen emphasizes the importance of partnering physical action with words: “I strongly recommend that the scene be found physically before you approach the verbal action […] you do not come into the room in order to talk to yourself [emphasis added].”

Generally, people aren’t actually physically still when they talk to themselves.

You will make life much easier for yourself if your words are accompanied by physical activity. You don’t have to finish the activity, but it will help in your character’s attempt to gain control over his/her circumstances.

Even though physical presence is essential, be aware of:

THE DANGER WITH PHYSICAL ACTIONS

Partnering actions with your words does not mean you have to physically act out the words. Or as Hagen puts it, “Don’t illustrate the life you are verbally fantasizing.” This is an easy trap us actors can fall into. You don’t need to show your audience what your words mean, which brings me to the next point of danger.

In a monologue, your character is alone. He/she knows exactly what is going on and doesn’t need to explain to anyone the whole story. But, obviously your audience still needs to understand the context. This is why Hagen advises to “let the humanness of your behaviour reveal the necessary events” in order for them to understand the story.

I’m aware of the trickiness of partnering words with actions, so allow me to share:

HELPFUL QUESTIONS TO ASK IN PREPARATION

Similar to Hagen’s previous advice to start with the physicality of the monologue first, ask yourself:

“What would I do here if I didn’t talk?”

Start with the physical presence first, and at some point, as Hagen reassures us, it’s going to be easy to start talking.

Consider what the real reason is of why you’re doing these things under the given circumstances in order to allow any verbal fantasy to take shape.

IN CONCLUSION

At the end of the day, don’t forget these guidelines aren’t meant to stress you out. They are there to help you make your performance as believable as possible in order to tell a story worth telling.

Have fun in your journey of exploring and imitating human behaviour, in order to let the stories you tell, be an inspiration to your audience.